For generations, Native American communities across North America have faced long, freezing winters with resilience and ingenuity. From the northern plains to the mountain valleys, surviving the cold meant more than enduring snow and ice; it required deep knowledge of the land, resourcefulness, and communal strength. Families depended on traditional skills to stay warm, preserve food, and protect themselves from harsh conditions.

Understanding how Native Americans survived winter reveals a legacy of adaptation and innovation. Techniques for insulation, winter shelter, layered clothing, and seasonal food storage varied across regions and tribes, shaped by local climates and available materials.

Today, these ancestral traditions continue to inspire and inform, as many Native families still experience the winter season as a time of hardship. Limited access to heating, warm clothing, and reliable infrastructure puts added strain on communities, especially those in remote or under-resourced areas.

In this resource, we’ll explore the ways Native peoples historically endured extreme cold, how those practices evolved over time, what’s being done now to help Native families meet modern winter challenges, and how we at Running Strong support these families today.

Traditional Ways Native Americans Survived Winter

For thousands of years, Native peoples across the continent developed region-specific methods for surviving cold climates. These strategies weren’t just about survival; they reflected a deep understanding of local ecology, community needs, and long-term sustainability. From shelter design to heating methods, every decision was informed by generations of experience and a close relationship with the land. Understanding how Native Americans survived winter begins with looking at the homes they built and the environments they adapted to.

Housing and Insulation

When facing subzero temperatures, wind exposure, and snow accumulation, shelter becomes more than a matter of comfort; it’s a matter of survival. For Native American communities, housing was intentionally designed to work with the environment, not against it. Materials were sourced from the land, and structures were adapted for thermal efficiency, durability, and practicality.

Insulation techniques varied depending on the region and available resources. Tribes in forested regions could rely on bark, saplings, and thatch, while Plains tribes used buffalo hides and long poles. These materials weren’t just used because they were accessible; they were chosen because they performed well in extreme climates. Builders understood how to trap heat, reduce airflow, and maximize interior warmth with minimal resources.

Shelters were often modified for seasonal use. Summer dwellings might be lighter and more open, while Native American winter homes were reinforced to resist snow, ice, and wind. Many tribes also designed their shelters with spiritual and symbolic significance in mind, incorporating traditional knowledge into the physical form.

In addition to the structures themselves, communities developed smart strategies for site placement. Winter homes were often built in low-lying areas, near tree lines, or against hills to block wind. Entryways were angled or covered to reduce cold drafts. Insulating the interior with layers of animal hides or woven mats added further protection from the elements.

The following types of housing illustrate the diversity and ingenuity of traditional winter shelter solutions across Native cultures.

Tipis

On the open plains, tribes like the Lakota, Cheyenne, and Blackfeet relied on tipis for year-round living, adapting them specifically for the demands of winter. These cone-shaped structures were covered in buffalo hides, which provided natural insulation while remaining breathable. The frame, made from long, straight lodgepole pines, was designed to be strong but flexible, capable of withstanding prairie winds and heavy snowfall.

Tipis included an inner lining of additional hides or canvas to trap warm air and insulate the living space. Fires were built in the center, with smoke escaping through a flap at the top. Entrances were oriented eastward to welcome the morning sun and shield against prevailing western winds. This eastward orientation also held cultural and spiritual significance, as many Plains cultures traditionally faced east during prayer. As described according to the State Historical Society of North Dakota, tipis were aerodynamic, efficient, and portable, making them ideal for nomadic life in an extreme environment.

Longhouses

Tribes in the Northeastern woodlands, including the Haudenosaunee (Iroquois Confederacy), lived in longhouses, which are large, semi-permanent structures built from saplings, bark, and other forest materials. These homes could be over 100 feet long and housed several generations of a single family under one roof.

Longhouses were constructed with thick wooden frames and bark siding, helping to trap and retain heat. Fires were placed along a central aisle, and smoke exited through vents in the roof. The shared space allowed families to pool resources and body heat, turning the home into a collective zone of warmth, safety, and storytelling. During winter, communal living inside longhouses strengthened social bonds and offered physical and emotional support.

Wigwams

Used by many tribes across the Eastern Woodlands and Great Lakes regions, wigwams were smaller, dome-shaped dwellings made from bent saplings covered in layers of bark, reed mats, or hides. These structures were often insulated with additional materials during winter and could be surprisingly warm for their size.

One distinctive feature of wigwams was the use of heated stones, which were placed in central fire pits or partially buried in the ground to warm the floor. In some cases, these stones were doused with water to create steam, mimicking the function of sweat lodges, ceremonial and spiritual spaces that also offered physical warmth. This method provided a reliable, low-tech way to generate heat during long, freezing nights.

Many Native communities also practiced seasonal relocation. In anticipation of winter, families would move to sheltered forested areas, valleys, or lowland regions where they were protected from wind and had better access to firewood, water, and game. These winter camps were carefully chosen and prepared months in advance, reflecting the long-term planning required to survive cold seasons without modern infrastructure.

Clothing and Staying Warm

A key survival strategy among Native Americans was layering garments crafted from animal hides and furs, designed to provide insulation and withstand harsh subzero conditions. Surviving winter meant protecting the body from harsh winds, freezing temperatures, and prolonged exposure. These snug-fitting garments trapped body heat while allowing for mobility during daily tasks, an effective defense against the cold.

Deerskin was one of the most commonly used materials. It is soft, flexible, and easy to process, making it ideal for shirts, leggings, moccasins, and robes. According to the Center for History and New Media, deerskin was a staple in traditional Native clothing, and even deer bones were repurposed as tools.

To add another layer of protection, some tribes applied bear or goose grease directly to their skin. This natural coating helped seal in warmth and shield exposed skin from windburn and frostbite, especially during long hunts or travel in severe cold.

Fur-lined hoods, mittens, and moccasins were also common in northern regions. Many garments were designed with layered construction, fur facing inward for insulation, and outer layers treated for wind resistance. These practical clothing systems were developed and refined over generations to ensure survival in the most unforgiving climates.

Food Storage and Sustenance

Food security during the winter months was critical. Tribes used seasonal abundance in the warmer months to prepare and store food that would carry them through long stretches of snow and ice. This required not just labor, but communal coordination and environmental awareness.

Native communities used a variety of methods to preserve food. Drying meat and fish in the sun or over low fires removed moisture to prevent spoilage. Smoking added flavor and extended shelf life even further. Fermentation was used for select foods, such as corn or roots, turning them into nutrient-rich staples that lasted well into the cold season.

Autumn was a key time for hunting and gathering. Communities focused on harvesting squash, beans, corn, and wild rice. These crops were stored in woven baskets, clay pots, or underground pits insulated with straw or bark. Meat from bison, deer, or elk was often dried and stored in rawhide bags, sometimes mixed with fat and berries to make high-energy pemmican.

Communal preparation was guided by observation and experience. Elders passed down knowledge on how to predict the length and severity of winter by watching signs in nature, such as the thickness of animal fur or migratory bird patterns. This foresight helped ensure that families had enough to last through storms, shortages, or delays in spring.

Deep Environmental Knowledge

Native survival strategies were grounded in deep, intergenerational knowledge of the natural world. Tribes read environmental cues to anticipate seasonal shifts and plan their movements and resources accordingly.

Weather forecasting often relied on animal behavior, cloud patterns, and changes in wind or temperature. Observing the early migration of birds, the behavior of squirrels, or the layering of certain tree barks could help determine when snow or cold fronts were approaching.

Many tribes moved camp seasonally, choosing winter sites for their access to wood, shelter from wind, and proximity to water and game. These migrations were not random but based on intimate familiarity with the land and its patterns.

Nature itself was a survival guide. Trees provided fuel, shelter material, and windbreaks. Rivers and lakes, even when frozen, were essential for food and hydration. By working with the rhythms of the environment rather than against them, Native communities developed highly adaptive, sustainable ways of living through the winter.

Ongoing Needs in Modern Native Communities

While traditional knowledge and resilience remain strong, many Native families today face winter without adequate resources. Modern technology, like electricity, insulated housing, and manufactured clothing, can help. But access to these essentials is far from guaranteed, especially in under-resourced areas.

On reservations like Pine Ridge in South Dakota, winter can bring months of subzero temperatures, snowdrifts, and icy winds. Many homes lack proper insulation or central heating. Families may rely on propane or wood stoves, and children often go to school without proper winter gear. The challenges of winter survival are not just historical; they continue today, often out of sight.

Winterwear Program – Protecting Children and Elders

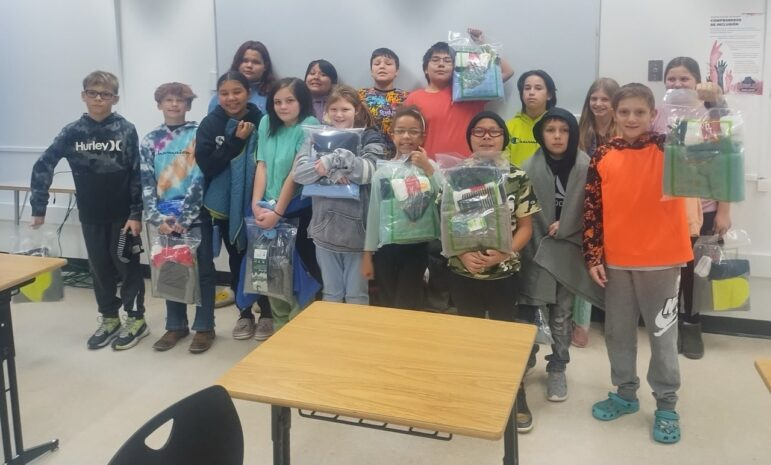

One of our most vital efforts is the Winterwear Program In-Kind Program, which helps protect some of the most vulnerable members of Native communities: children and elders. During fiscal years 2023 and 2024, this program distributed 34,820 coats, boots, and socks across 16 tribal communities throughout Indian Country.

In total, over 33,000 winter coats, nearly 30,000 pairs of snow boots, and more than 20,000 hat, glove, and scarf kits were delivered. These items don’t just provide warmth, they provide comfort.

Theresa Halvorson-Lee of the Division of Indian Work in Minnesota put it powerfully:

“A warm coat is not just a piece of clothing – it’s a shield against the biting cold and a lifeline for children walking to school or playing outside.”

One of the children who benefited is 8-year-old Reuben, who showed up to a winter coat distribution event wearing only a thin hoodie. Volunteers noticed how cold and quiet he was. When he received a brand-new insulated jacket, he smiled and said, “Now I won’t be cold anymore.” His joy was simple, but the impact was profound.

Heat Match Program – Help for Harsh Climates

In addition to clothing, heating is a critical concern for Native families living in regions where winter lasts half the year or more. The Heat Match Program provides life-saving support by helping households afford essential fuel for warmth and cooking.

During FY23 and FY24, we supported over 4,000 families through this program. Each household received a 1:4 match, meaning that families provided $100 towards their own bills and we matched it x4 for $400 in assistance to help cover propane and electric costs during the coldest months.

This program is especially important on the Pine Ridge Reservation, where winters are severe, and many homes lack reliable heating systems. With limited income and rising fuel costs, families often face impossible choices between heating, food, and other necessities. The Heat Match Program offers not just financial support, but peace of mind and safety in a dangerously cold environment.

Why This Support Matters

Staying warm is not just about physical safety. It is about comfort, peace of mind, and the ability to focus on life beyond basic survival. In Native communities, warmth represents more than protection from the cold; it reflects care, tradition, and the strength of community.

Access to proper winter clothing and reliable heat allows children to attend school without distraction, elders to rest safely in their homes, and families to come together without the constant strain of freezing temperatures. These resources help ensure that winter is not a time of hardship, but a season that can be endured with resilience and hope.

When you support programs like the Winterwear and Heat Match initiatives, you’re helping restore that peace of mind. You’re showing that no family should have to compromise on warmth and well-being, and that everyone deserves the comfort of a safe, supported home during the coldest months of the year.

How You Can Help Native Families Stay Warm

Each winter, thousands of Native children, elders, and families face freezing temperatures without the basic resources they need. A warm coat or a full propane tank can be the difference between hardship and relief, between anxiety and peace of mind.

You can be part of the solution.

By supporting Running Strong’s winter programs, you help deliver real, tangible aid, coats, boots, gloves, and heating assistance to Native communities where it’s needed most. Your contribution helps keep kids safe on their way to school, protects elders during the coldest nights, and strengthens communities facing harsh conditions with strength and courage.

If you’d like to make a difference, donate to support this work and help us continue reaching families across Indian Country. Sharing this resource is another way to raise awareness and bring others into the circle of support.

Together, we can help ensure no Native family has to face winter alone.